Stop Telling Muslim Women To Be Safe

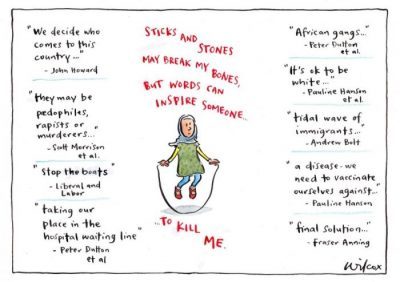

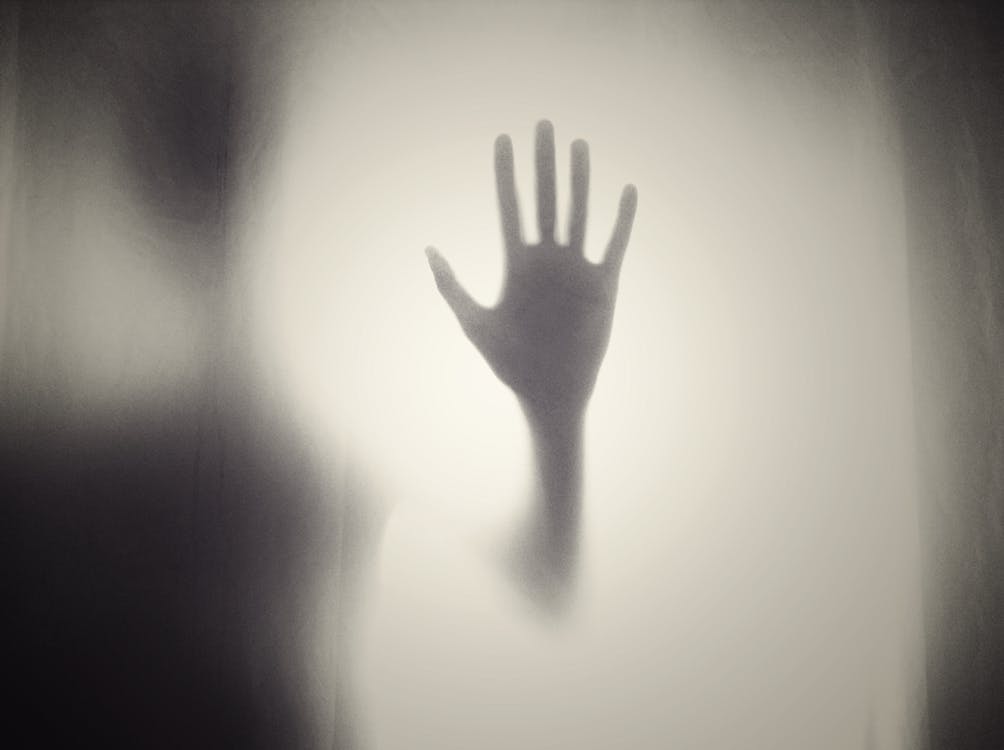

Hijabi women are the most visible Muslims who face the brunt of Islamophobia in western societies, but to help them is not to control their movement.

In the aftermath of teenage Nabra Hassanen’s murder in an anti-Muslim road rage incident, as the sympathy and grief was expressed throughout the western Muslim world, so were warnings directed towards sisters to watch where they’re going.

Statuses and speeches circulated reminding us: ‘sisters be vigilant’, ‘sisters be safe’, as though we could actually determine our own security, as though we could make safer decisions, whatever those may be.

While such goodwill sentiments are welcome, they can often translate as a shift in burden from the state, community and support networks, to the individual.

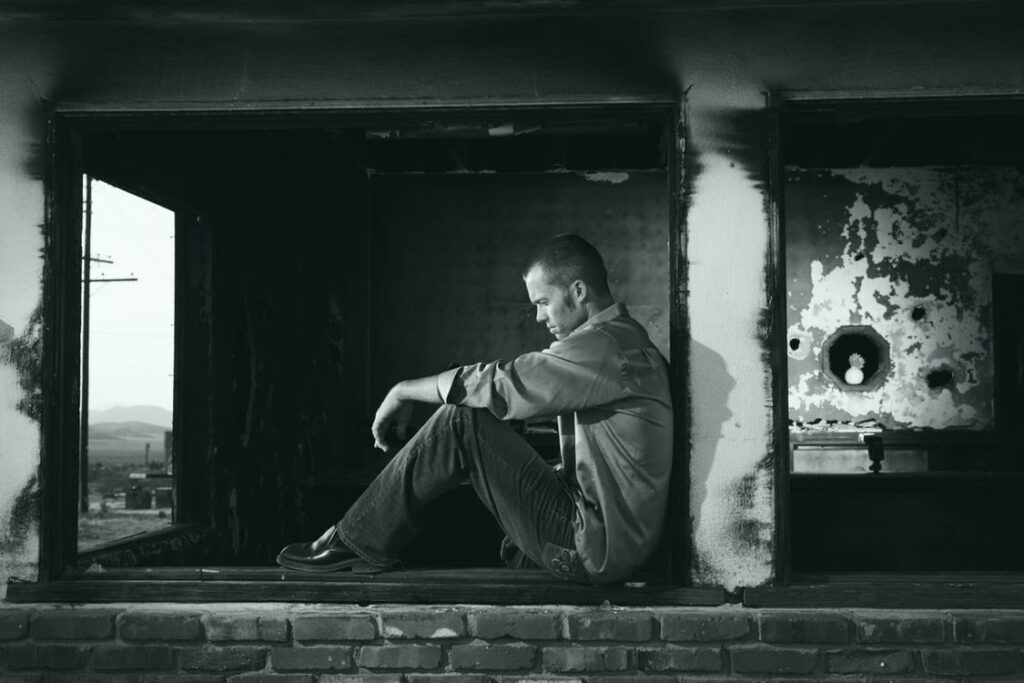

They send a message that you, alone, are responsible for your own protection. It makes women feel isolated and suffocated.

As many of us are already feeling afraid and insecure, ‘be safe’ can work as an additional violence; a reminder that we are unsafe and that we are vulnerable and a target. Instead of acting as a show of strength, it reminds us of how weak we are; and no one wants to feel weak.

This can result in learned helplessness, instead of the intended vigilance that supporters want to encourage Muslim women to develop.

Ordering women to be safe has long been critiqued by women’s advocates, who argue that telling women how to be safe teaches young women that they are the ones that cause bad things to happen to them – that it is their fault.

Learned helplessness is a social theory that is used to explain repeated victimisation and is regularly applied to many victims of violence, particularly women subjected to domestic violence. It explains the way in which after a series of attempts to escape violence, people eventually give up these attempts even when the reality changes. Learned helplessness refers to developing skewed perceptions of reality to a toxic and life-threatening environment.

To counter learned helplessness, women’s advocates teach women statistics that alter their heightened fear perceptions. For example, in response to cultural controls on women which blame them for becoming victims of rape, women’s advocate groups have taught us that statistically, the most dangerous threat to us are actually men we know, not strangers.

It’s important to keep this in mind when sharing and responding to anti-Muslim racism. Though it is vital that we cover these stories so that Islamophobic attacks can be treated and prosecuted as the hate crimes that they are, these stories should not turn into moral panics about the danger to women.

Just as we are more likely to die from slipping in the bathroom than from terrorism, the likelihood of Muslim women being the victims of physically violent Islamophobic attacks is also minute – in comparison to other threats.

We should not allow our fear to rule the way in which we live our lives and the way in which we make decisions. While we lack many of the privileges enjoyed by those with proximity to whiteness, some of us from middle-class migrant backgrounds still do have the privilege of safety and we cannot over-exaggerate the threats we face as this actually harms us as young Muslim women.

Muslim women are already subjected to, and fight to resist, the regular cultural controls directed at them. We have been trained to not act dangerously, whether this means shrinking ourselves online and in physical spaces, toning down our voices to avoid provoking more powerful figures, avoiding presence in less welcoming spaces, and choosing female-friendly careers.

As young Muslim women, we should not allow Islamophobic attacks to be exploited and turn into further controls on us. Yes those who love us will want us to be more safe – but at what cost?

Are we going to stop going to the mosque, are we going to not work in the city, are we going to not have any public profile that will bring attention towards us, to ‘guarantee’ safety?

Obviously, to most women, these are non-options. As second-generation immigrants, we have already seen our mothers take a back-seat in a new country that wanted their labour but not their voices or citizenship input. We cannot afford to also be sidelined back behind men in our community.

Muslim men who are visibly Muslim are also targets to hate crimes, but their visibility is hardly in question. I do not see anyone suggesting that men should not participate in Muslim spaces, mosques or work in more urban spaces to avoid Islamophobia.

Their rights to career and participation come first, compared to those of Muslim women’s who appear to be regarded as options to those who want their ‘safety’, but not much else.

Sadly, the most troubling consequence from continuing to tell Muslim women to be safe, and heightening this fear, is that from the exhaustion of trying to navigate security and life, removing the hijab becomes the only possible path forward. The only way they can be safe and continue their lives as usual – because following the skewed reality perceptions, what other options do they have if everyone is telling them to take action to ‘be safe’?

Instead of putting the pressure and responsibility of safety on young women, community leaders should be pressuring authorities and working alongside women’s support groups to ensure more safety and resilience training for Muslim women.

That is the only way to ensure there is space left for Muslim women in the public sphere.

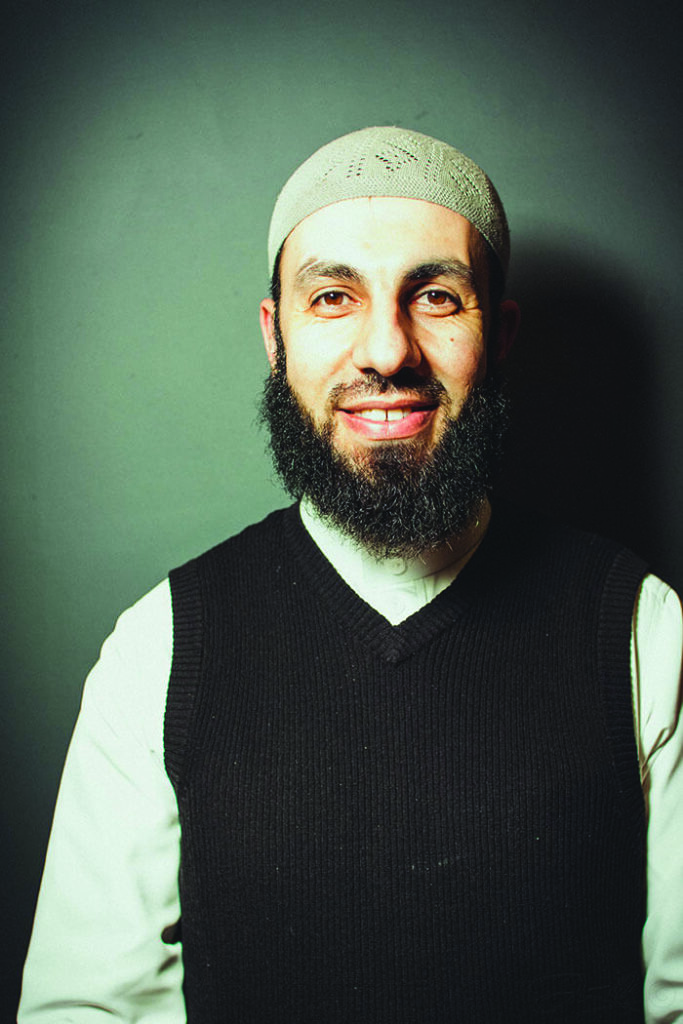

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tasnim Sammak

Tasnim Sammak is a Palestinian Australian. She has a Bachelor of Arts (Politics) and Education from Monash University. After graduating, she began a new journey into motherhood and has two young sons. She co-founded and is now the director of the first Muslim youth mentoring program in Australia, the Igniting Dreams Together Mentoring Program. She also served on the Islamic Council of Victoria’s Office For Women board. Currently, she is studying Honours in Education, researching the impact of Islamophobia on Australian Muslim students. She hopes to become a researcher and author on issues challenging the upbringing of Muslim youth in Australia

Originally printed in Podium Magazine Edition 2, published in 2017.