Ramadan: An Ode To Our Prophet’s (PBUH) Hunger

When I reflect on the imagery in ‘Ramadan spirit’, I often envision Muslim volunteers distributing meat to poorer families in Jordan. That’s an association I formed in my early years, as this was part of the Islamic culture that some groups sought to bring to life in Muslim-majority nations.

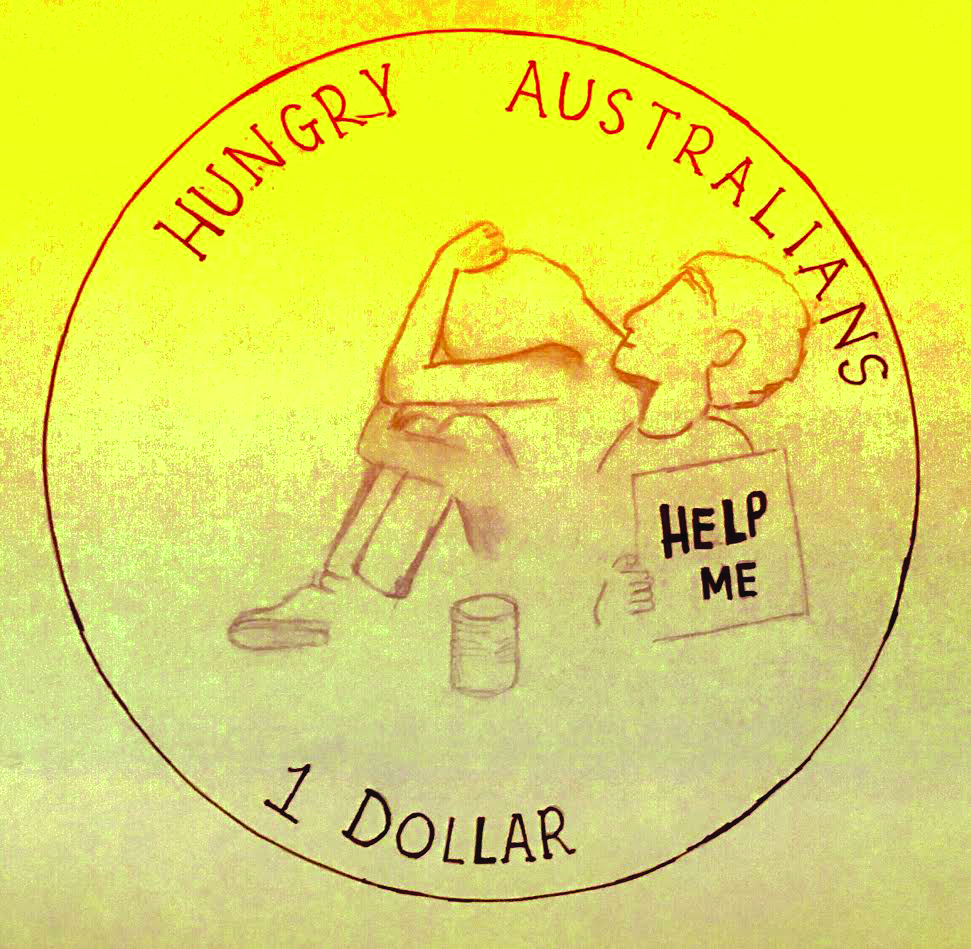

Ramadan, the month of abstaining from food, was immediately associated with assisting those who have less in the neighbourhood. The communal spirit was intrinsic to Ramadan; it was a natural extension that when one is fasting, when one gets up for suhoor, they empathise with families who have nothing for iftar or suhoor.

Living in ‘middle’ Australia, we can often feel very removed from the reality of poverty, even though Ramadan essentially is an ode to the hungry. Every single person, across the world, is required to elevate the status of the poor and hungry by partaking in the fast.

The fast is supposed to be a reminder to those of us who do afford full meals to never go about life imagining that this is everyone’s reality. While the food industry glamourises food and sets up an ideal class of cooks that everyone aspires to be like, Allah SWT instead instructs us to practice the most stigmatised experience, by living with the hunger pangs of the poor, for a full month.

The problem is, we don’t actually allow ourselves to practice Ramadan with the intent of fasting, as we occupy our day with meal-planning, learning ‘energy-preserving’ recipes, seeking out organic produce and products to compensate for our skipped meals.

As we lift our eating game, we miss the principle of eating less – so that when we suppress the physical pangs, we train our bodies to rise above the glamourisation of eating and ‘foodies’ that has become crucial to our modern social conditioning. Yes, we say no to brunches in Ramadan, or Melbourne’s best coffee orders, but it is harder for us to make the claim that we fast to empathise with the poor if our families are serving up full menus, suhoor and iftar.

If we reflect back on the way the Prophet PBUH broke the fast and prepared for suhoor, we learn that his diet was humble in a way that does not compensate for the day’s hunger. What we do, though, is eat in two meals, what we normally would throughout the entire day (and more, right). What we know is that the Prophet PBUH would break his fast with dates, milk or water, before he went to pray Maghrib. Ironically, we have actually missed that this would constitute his full iftar meal – he would not resume eating afterwards!

We know this from a few narrations from the Sahaba, but one that proves this point really vividly is a story told by Anas ibn Malik RA, one of the companions who had served the Prophet PBUH for many years and knew the Prophet’s PBUH habits very well.

One day, Anas RA knew that the Prophet PBUH was fasting, so he arranged for his iftar. Anas RA kept the milk and dates ready, and the milk and dates were only sufficient for the Prophet’s iftar. However, at the time of iftar, the Prophet PBUH did not appear for the breaking of the fast, so Anas RA thought that he may have accepted an invitation from someone and broken his fast elsewhere and ate the food himself and decided to go sleep.

Later, the Prophet PBUH entered the house with another companion. Anas RA asked the companion discreetly whether the Prophet PBUH had already eaten. “No,” replied the companion softly. “The Prophet PBUH had to deal with some urgent work. He was delayed so much that he is now late for iftar.”

Anas RA felt so ashamed – there were no more dates or milk! The Prophet PBUH had already sensed that Anas RA was hesitant in offering him food as this was not like Anas RA at all, but behaved as though he was not hungry at all. Anas RA used to say: “The Messenger of Allah PBUH never mentioned this incident during his lifetime to anyone”.

What I find remarkable in this story is that the Prophet PBUH not only went hungry for the night, he intended to break his fast on very little, anyway.

We cannot even contrast our fasting experience because doing this itself is absurd. There is no commonality, we are completely out of the sunnah that to compare is misrepresentative itself in that it denies the reality of our consumerist culture.

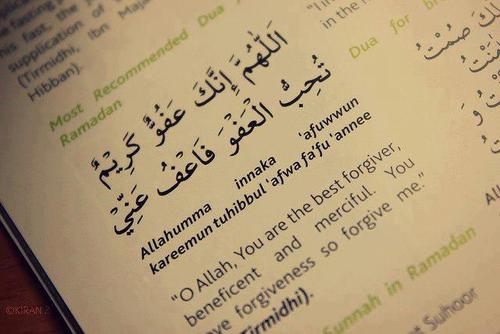

Ramadan invites us to a one month challenge “so that you may have taqwa” [2:183], by controlling our desires. We are thus encouraged to attain this through disciplining ourselves against the dominant neo-liberal cultures feeding on our desire for more – more food, more quality, more fresh, more diverse.

It is an invitation to switch off from these pressures, and to deal with urgent work – whether this is spiritual or community work, and forget about the urgent need to eat, as in our Prophet’s PBUH example. Maybe even start working on feeding the hungry in our suburbs.

There is no better liberation, if only we were hungry enough to taste it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tasnim Sammak

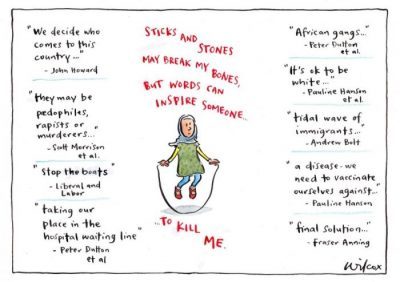

Tasnim Sammak is a Palestinian Australian. She has a Bachelor of Arts (Politics) and Education from Monash University. After graduating, she began a new journey into motherhood and has two young sons. She co-founded and is now the director of the first Muslim youth mentoring program in Australia, the Igniting Dreams Together Mentoring Program. She also served on the Islamic Council of Victoria’s Office For Women board. Currently, she is studying Honours in Education, researching the impact of Islamophobia on Australian Muslim students. She hopes to become a researcher and author on issues challenging the upbringing of Muslim youth in Australia

Originally printed in Podium Magazine Edition 1, published in 2017.